Remarkable Creature: The Vaquita

Introduction

Vaquita caught in a fishing net

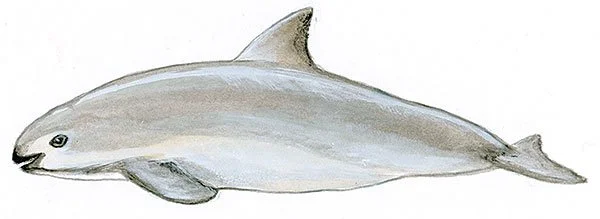

The vaquita is a critically endangered porpoise that can be found in the northern end of the Gulf of California in Baja California, Mexico. Although similar to dolphins, porpoises are more closely related to narwhals and belugas than to the true dolphins.

What makes the vaquita special?

Well, by the time you finish reading this article there may in fact not be any left in the world. It is estimated that only ten vaquitas are still alive, and no one knows for sure how many are in fact left.

Let’s take a look at what is happening:

The Panda of the Sea

The vaquita displays a black lip liner just skirting the edges of its mouth. Its eyes are cradled in circular black holes, giving it the nickname ‘Panda of the Sea’. Vaquitas are generally seen alone or in pairs, often with a calf.

They are generalists, foraging on a variety of demersal fish species, crustaceans, and squids, though benthic fish (fish that live right on the ocean floor) such as grunts and croakers make up most of the diet.

Vaquitas live in shallow, turbid waters of less than 150 m (~450 ft) depth and remain one of the most cryptic creatures in the world. They exhibit extremely shy behavior, which limits sightings and interactions. It took many years for scientists to learn what we know today about the vaquita.

Current knowledge is based on sightings of live animals, observations of stranded or trapped animals, and necropsies.

While we still have much to learn, there is little time remaining – the extinction of the vaquita is almost a certainty.

“Souls of the Vermillon Sea”

My research into the vaquita included watching a powerful 30-minute documentary by Matthew Podolsky and Sean Bogle, called “Souls of the Vermillon Sea”.

Set in a small fishing community in Baja California, Mexico, the film provides a valuable perspective at the intersection of human sustenance, world trade, and marine life. It highlights the threat of extinction of the vaquita by the illegal fishing of the totoaba, a species of fish.

Formerly abundant and subject to an intensive fishery, the totoaba has become rare, and is listed by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora.

A key threat to the totoaba is indeed from human poaching: its swim bladder is a valuable commodity, as it is considered a delicacy in Chinese cuisine, while the meat is sought-after for making soups. It can fetch extremely high prices as it is erroneously believed by many in China to be a treatment for fertility, circulatory, and skin problems.

Economic forces such as market demand for the totoaba, and the difficulty in enforcing anti-poaching laws in rural, seaside communities with little alternatives to fishing for whatever brings the highest value, are key parts of the story. They highlight the peril that many animal species like the vaquita find themselves in: caught in a physical and metaphorical net with no way to escape or survive.

A Market-Based (Albeit Contested) Solution

In September 2024, a possible solution emerged to the issue of endangered vaquitas: alternative poaching methods for the totoaba, that may dramatically reduce the odds of actually inadvertently capturing vaquitas. The innovative conservation approach to saving the vaquita seeks to work with, rather than against, local fishers.

Indeed, the Cetacean Action Treasury (CAT) is pioneering a harm-reduction strategy that challenges traditional conservation methods. Instead of strictly enforcing fishing bans, they're encouraging fishers to switch from gillnets to cimbra, a hook-and-line fishing technique that minimally impacts marine life. By using cimbra, illegal fishermen can catch fewer but more valuable totoaba while avoiding accidental marine mammal deaths. As of September 2024, CAT has apparently recruited about 20 "vaquita-safe" poachers, demonstrating the potential of this collaborative method.

The solution is not without controversy. Conservation organizations like Sea Shepherd oppose any totoaba fishing, yet CAT's strategy addresses both ecological and economic concerns. By offering fishers a financially viable alternative and avoiding confrontational enforcement, they aim to protect the vaquita while supporting local livelihoods. The approach recognizes the complex economic realities of fishing communities and seeks to create a mutually beneficial solution.

The proposed method represents a shift from traditional conservation tactics. Rather than viewing fishers as adversaries, it positions them as potential allies in marine preservation. Thus, fishers are not environmental activists, nor destructive actors, but pragmatic people open to methods that can sustain both their income and marine ecosystems.

As the vaquita faces potential extinction, this innovative strategy offers a glimmer of hope—a potential path forward that acknowledges the intricate relationship between human survival and marine conservation.

Conclusion

What should we do with all this? Can the cute and cuddly vaquita be saved? George Carlin’s deeply sarcastic, but on-point comedy bit on the topic of saving endangered species is relevant and informative, and I include it below. Here’s a quick excerpt : “Saving endangered species is just one more arrogant attempt by humans to control nature. It’s arrogant meddling, it’s what got us in trouble in the first place.”

The awareness of critically endangered animals disappearing due to human interactions should indeed serve as a wakeup call. And in my view, rather than succumbing to despair or knee-jerk reaction to protect this or that individual species, this recognition should motivate pretty much everyone to become environmental activists in a more general sense.

To be clear, we should absolutely do what we can to protect our environment, biodiversity, and be better stewards of our one, beautiful planet. But as George Carlin hints at, anything involving nature and the environment is best done with a heavy dose of realism and humility. And yes, even a bit of levity.

Sources: